China’s love and hate relationship with gaming and esports can be tracked all the way to the ’90s when gaming and esports are not a thing and still considered taboo at times. Today, China as a nation played a significant role in the realm of esports.

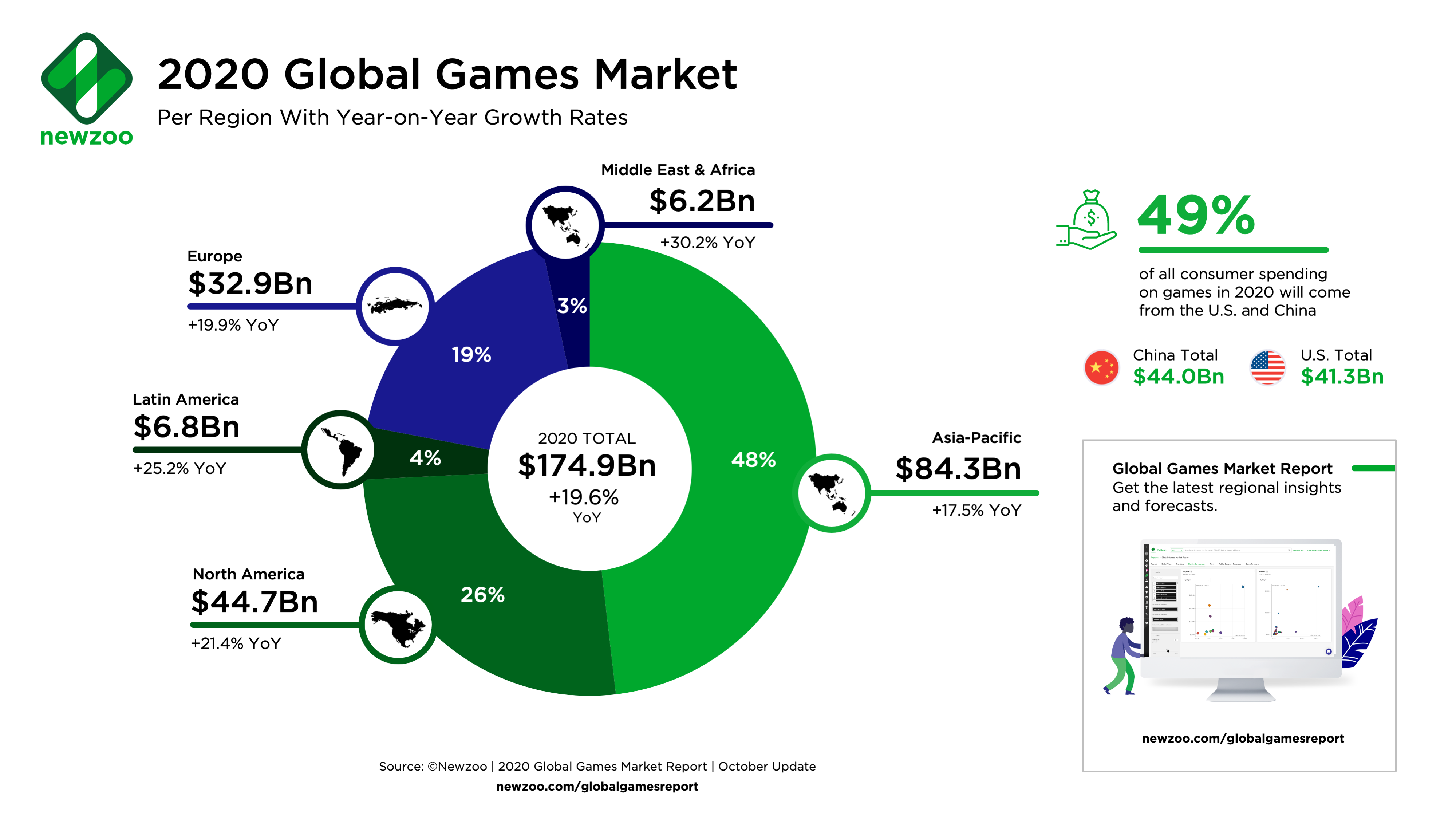

In fact, China is now recognized as the most prominent nation in the video game industry globally and the most potent challenger to the previously dominant market, the United States. They are currently the largest market by revenues, with total revenues of US$385,1 million in 2020, followed by North America, with total revenues of US$252,8 million.

In the past six months, we saw the Chinese esports industry emerging from the pandemic’s abyss to stage the year’s largest esports competition – the League of Legends World Championship – in Shanghai, as well as a US$100 million Series B investment in a Chinese esports company. But how did it all begin? Was the path to where they are now straightforward?

Gaming Before 2009: Massive number of negativity around the industry

Most people were unaware that before 2009, gaming and esports were viewed mainly negatively. It was often regarded as obscene, abusive, ineffective, and deficient in cultural refinement. To “protect the ideological thinking and morality of young people”, strict laws and regulations were in effect all over the place.

Censorship has been a source of contention since the 1980s when the first arcade games were introduced into the Chinese market. The general perception of gaming as a disruptive activity and a danger to addictive lifestyles prompted the development of policies in the 1990s, namely “Government Notice Strengthening the Regulation of Billiards and Video Games” by the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television of People’s Republic of China, and various other policies in the future years.

Many international games were prohibited and could not be brought into China during this period, while domestic games received official warnings, forcing developers to change game material linked to the portrayal of violence and sex.

Chinese news outlets, primarily state-owned publications, stoke the fires by spreading negativity about gaming and esports. The term “gaming” is often associated with societal taboos, crime, brutality, illiteracy, and gambling.

The peak was The Lanjisu Fire accident — a 2002 internet cafe fire in Beijing that killed 25 young people — has been part of China’s collective memory. It was a watershed moment in China’s internet cafe period. The Lanjisu Fire elevated the issue of China’s internet cafes to a national level. Not only were the unhealthy conditions concerning, but so was the effect of internet cafes on China’s youth, with students spending days on end playing video games in these smoky halls, contributing to an increase in school absenteeism and internet addiction.

The accident provided an opportunity for the party-state to react to a moral outrage sparked by the media and backed up by concerned parents over the risks of internet cafes frequented by alleged teen-hooligans.

The fire prompted a massive ban on illegal internet cafes. The Beijing authorities initiated a drive to halt the construction of new internet cafes and screen all established internet cafes one by one and shutter all unlicensed enterprises and confiscate their operating tools effectively. Approximately 400,000 internet cafes were closed across the nation.

Moral Panic: The dark era of immoral practice

Negative public discourse on gaming in Chinese culture resulted in a state of moral panic, which Stanley Cohen defines as an exaggerated collective response to something that described as a threat to cultural values and interests.

We investigated a plethora of news stories about gaming and esports that seemed negative, especially those from 2009 or earlier. It was easy to find one thanks to Google Time Machine Feature.

- Sina – 青少年沉迷网络游戏致恶性事件频发 (Teenagers addicted to online games cause frequent vicious incidents) – 24/12/09

- Diyifanwen – 青少年沉迷网络游戏致恶性事件频发 (The Dangers of Indulging in Online Games) – 1/10/09

These were some of the findings, which did not contain television broadcasts that citizens viewed on a regular basis. There were also a lot of questions raised on Baidu, China’s Quora-like website, about the effects and concerns of gaming addiction, which was very widespread. But the point is that gaming was seen negatively by Chinese parents.

At one point, the moral panic became so intense that Yang Yongxin, a Chinese clinical psychiatrist who advocated and practised electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as a cure for alleged internet addiction in adolescents. He operated the Internet Addiction Treatment Center at a hospital, which has been closed since August 2016.

According to media reports, families of adolescent patients admitted to the hospital were charged CN¥5,500 (US$854) a month for therapy with a mixture of psychological drugs and ECT, nicknamed “brain-waking treatment” by Yang.

He treated 3000 children before the practice was prohibited by the Chinese Ministry of Health. Yang claimed that 96% of his patients had shown signs of improvement, a figure that was questioned by the Chinese media. Since the ban, Yang had used “low-frequency pulse therapy”, a treatment of his own devising alleged by former patients to be more painful than ECT. In 2016, the practice claimed to have treated more than 6000 adolescents.

The Turning Point: The Presence of Esports

2009 was a watershed moment for China, and thus likely for the rest of Asia as well. It was the year that the government softened its policies and controls by granting approval for the distribution of many games, including League of Legends and Dota 2. However, the agreement was non-Chinese developers were only allowed to distribute their games only through vendors affiliated with one of the China-based gaming publishers.

NetEase, Tencent, and Perfect World were three dominant forces in this matter. The former has the distribution rights to Minecraft, World of Warcraft, StarCraft II, Overwatch, and several other games. Meanwhile, in China, the latter is the sole distributor of Valve’s games Dota 2 and Counter-Strike: Global Offensive.

This strategy aimed to improve China’s soft power by encouraging the creation of more domestic games with funds collected by vendors and gaming agency commissioning and taxation. This has aided the accelerated development of local gaming companies, strengthened societal perceptions of interest in the game industry, and significantly raised total domestic revenues by a lot.

Today: China’s Gaming Industry Overlap the United States, which opened up new possibilities for esports

According to Statista, in 2021, China is expected to account for 32% of all global game industry sales.

The gross sales of China’s games industry rose by 20% year on year to US$43 billion in 2020. Global game sales are forecasted to reach US$154 billion in 2021, with China accounting for US$49 billion of that total. It was also revealed that the mobile games industry had increased eightfold in six years, rising from US$4.2 billion in 2014 to US$32.4 billion in 2020.

The Future: China’s Strategic Plan for Esports in Public Sectors

No country has made this big of a commitment to the development of esports as the Chinese. The government encourages domestic esports development as a source of national pride, and unlike soccer or other common consumer sports, China dominates esports.

China’s desire to become the centre of esports can be seen in its efforts to align with and be more welcoming to esports. Regulations have been eased, and government investment and funding have also played a significant role. Even cities in China are vying to be China’s esports capital.

In eastern China’s Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou unveiled the country’s first esports town in November 2018. The Chinese government built and will oversee the plant, which spans approximately 17,000 square meters and is estimated to have cost roughly CN¥2 billion (US$310 million) to construct.

Chongqing, based in Western China, has already hosted various large-scale tournaments, including The Chongqing Major Dota 2 and StarLadder & ImbaTV Invitational Chongqing CS:GO 2018. The number of events organized in these cities is expected to increase after the pandemic.

Meanwhile, Shanghai has planned to open The Shanghai International New Cultural and Creative Esports Center, which would cost CN¥5,8 billion (US$900 million) and cover an area of 500,000 square meters. It is intended to serve as a centre for esports teams and businesses and will have a hotel.

The Future: Private Sector Go Hand in Hand with The Government

Besides the public sector, China has urged domestic technology behemoths, most prominently Tencent and Alibaba, to increase their funding and investment in gaming and esports.

Tencent, China’s most valuable gaming company, operates a number of game studios, including Riot Games, creators of League of Legends, VALORANT, and stakes in Activision Blizzard Ubisoft, Supercell, and many others.

Additionally, the growth has expanded to the root, as Chinese universities have launched esports modules and majors to regenerate more esports players in the future. Peking University and Communication University of China are some of the prominent educational institutions that have introduced esports programs.

Closing: China’s Circle of Success in Esports

With China’s strength and the funding of both the public and private sectors, it will not be long before China achieves its goal of being the center of esports. 2020 has already shown to be a spark for established phenomena and esports in China can only continue to grow and spread through all sectors in the midst of a global pandemic.

Every week, large tournaments are held, brands want to be a part of it, youth interest in esports is higher than ever, and governmental support would back them all up to continue esports’ smooth and ever-growing trajectory in this country. This circle represents China’s greatest strength in achieving its ambition in esports in the coming years.

Feat Image Credit: ESL